“Too Old for That?” – How Ageism Impacts Physical Activity Levels in Older Adults

Would you describe yourself as ageist?

According to Age Without Limits, 40% of the general public have not really thought about it before. However, ageism is the most widespread form of discrimination. 1

We know that physical activity is vital at all stages of life, including in our later years (There are enough studies that highlight the benefits, so I am not going to elaborate on that point here!). However, as we age, we are less likely to be physically active. Physical activity is much more than just keeping fit. It provides opportunities to connect with people and the wider community, provides social interaction and helps to combat loneliness. It also provides opportunities to learn new skills and can improve cognitive function – all things that we know support healthy ageing.

I am very conscious that as I write this as a 28-year-old, I have no personal lived experience of ageism. However, we likely all know and care about an older adult, and hopefully, we’ll be lucky enough to become older adults ourselves one day, so I believe this is a subject that we can all relate to. Through my work on Live Longer Better Gloucestershire, I increasingly find myself having more and more conversations around this topic. As a result, a couple of colleagues and I co-delivered a lunch and learn to the Active Gloucestershire team, sharing some of our insight and learnings about ageism, which has further inspired this blog on ageism and its possible impact on physical activity levels in older adults.

What is Ageism — and where does it show up?

A quick google search defines ageism as ‘to prejudice or discrimination on the grounds of a person’s age’. Under the Equality Act (2010), age is a protected characteristic, so any such discrimination can have legal consequences. Sadly, however, ageism is largely accepted within society. Ageism can impact anyone, but for the purpose of this blog, I am going to refer to ageism towards older people (I am also going to refrain from using an age to define an older person). One thing we all have in common is that we all experience the ageing process, and whilst the stages are different, the process is the same. As a result, it’s fair to say, if you hold ageist beliefs, you are essentially discriminating against your future self.

Ageism can present in three ways: institutional ageism, interpersonal ageism or self-directed ageism 2.

Institutional ageism produces systemic barriers for older people through policies and procedures within organisations and societal norms. It can appear in workplaces and healthcare systems. If we look at societal norms, we can also refer to how and when older people are represented through media.

Some examples of Institutional ageism include:

- public spaces lacking age-friendly infrastructure

- doctors who are less likely to refer older people with suicidal thoughts to mental health treatment3

- lack of representation of older people within media and/or reinforcement of ageist stereotypes within media

- upper age limits to services

Interpersonal ageism refers to ageism that is apparent when we interact with others, for example holding negative thoughts about someone based purely on their age. Self-directed ageism refers to when an individual internalises ageist beliefs or attitudes and applies these beliefs to themselves. Both can look very similar with some examples including phrases such as:

- “They/I can’t do that because they/I am too old”

- “You look great ‘for your age’”

- “They are having a senior moment / I am having a senior moment”

- “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks”

The impact of ageism:

There are many studies that highlight the impact of ageism, including an American study that found that people with a positive self-perception of ageing lived 7.5 years longer than those with less positive self-perception.4 Among older people, ageism is also associated with poorer physical and mental health, increased social isolation and loneliness, greater financial insecurity, decreased quality of life and premature death.5

Self-directed ageism is often a result of exposure to ageism from institutions and through interactions, meaning that we become what we digest. If we are constantly seeing and hearing that we should ‘slow down’ as we age and that older adults are a ‘burden’, then to me, it is more likely that we are going to impose those beliefs upon ourselves.

I have talked a bit about the wider impacts of ageism, but how does ageism impact physical activity levels?

Institutional ageism: If policies, strategies or systemic structures do not consider the health and wellbeing of older adults, the less likely they are to be physically active. There is a big campaign driven by The Centre for Ageing Better around the importance of developing ‘Age Friendly Communities’. Becoming age friendly means ensuring that the needs of older people are considered, and in terms of physical activity, ensures that older people can engage with activities they enjoy, stay in their own home and contribute to their community for as long as possible. This, in turn, means that older people are more likely to visit or attend said spaces. We need to ensure that communities have age-appropriate activities, and that these activities and spaces are advertised in a way that helps older people feel as though they belong there.

Interpersonal & self-directed ageism: Have you ever told an older person that it might be time to “slow down”? It’s a common phrase, but have you ever stopped to ask why we say it? Often, it is just something we assume is appropriate as people age. However, this seemingly innocent remark could cause more damage than we think as it reinforces ageist beliefs through everyday conversation. Some older people may be motivated to remain active or start a new hobby, but if they’re repeatedly told to take it easy by family or friends, such messages could discourage them from engaging in the new activity.

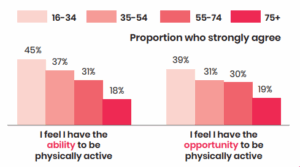

The latest Active Lives Survey from Sport England highlights that those who strongly agree with the statements ‘I feel I have the ability to be physically active’ and ‘I feel I have the opportunity to be physically active’ both drop with age (see below)6:

Whilst this does not show a direct causality, it is probable, and my belief, that self-directed ageism has some role to play in influencing these attitudes as it fits ageist and societal stereotypes i.e. slowing down and participating less as we age. As mentioned earlier, we know that the attitudes that we hold have an impact on our quality of life, therefore, I believe that negative attitudes can create a self-fulfilling prophecy, whereby older adults reinforce stereotypes by reducing their physical activity levels.

Ageism is unfair. It plays a role in how we all think about and act towards ageing. The result? A cycle of:

Ageism → Less activity → Physical decline → Reinforced stereotypes → More ageism

By shifting language, redesigning spaces and policies, and changing the narrative of ageing away from decline towards opportunity, we can break the cycle. As mentioned at the beginning of this blog, physical activity is about so much more than just keeping fit, it plays a pivotal role in strengthening communities, improving cognition and providing purpose. Role modelling activity in later life also helps challenge ageist societal norms.

Ageism affects us all, whether this be now or someday in the future. By rejecting stereotypes and consciously supporting older adults’ participation in physical activity, we can create communities where everyone thrives and where physical activity and movement becomes the norm for people of all.

3 Ageism: How can I tackle age discrimination and stereotypes?

4 Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, Kasl SV. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002 Aug;83(2):261-70. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261. PMID: 12150226.

5 Ageism is a global challenge: UN

6 Active Lives Adults Survey Report Novemeber 2023-24 Report

.